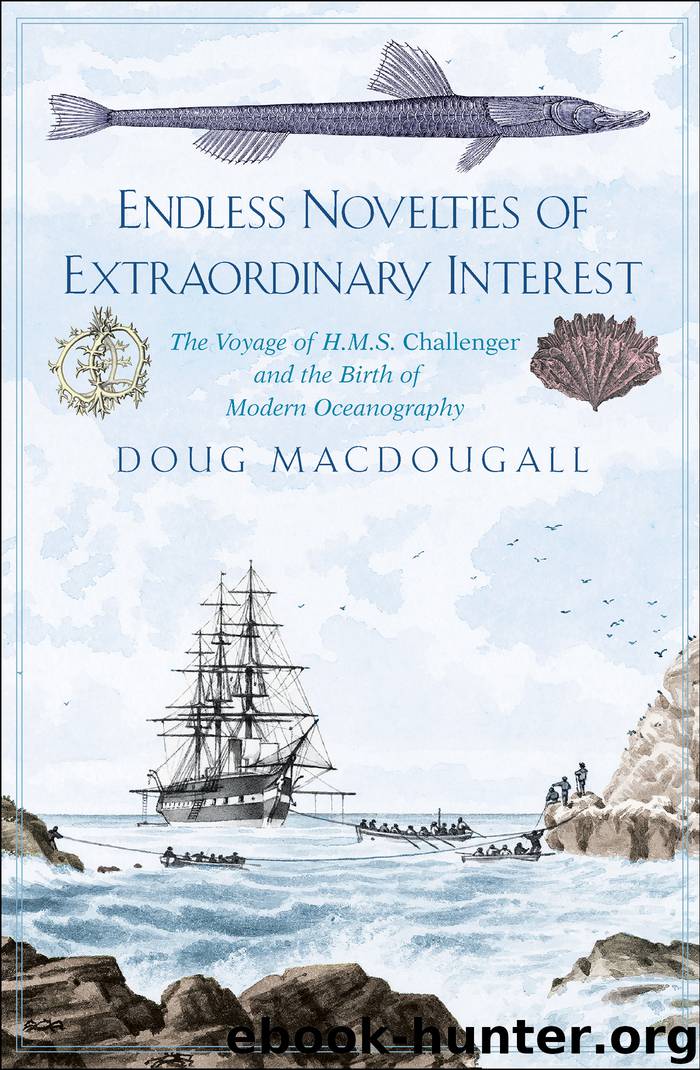

Endless Novelties of Extraordinary Interest by Doug Macdougall

Author:Doug Macdougall

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Yale University Press

Published: 2019-10-27T16:00:00+00:00

eight THE NATIVES

On March 4, 1874, the crew of Challenger said good-bye to the last Antarctic iceberg they would see on the voyage. They were en route to Australia and the Pacific, and no one was particularly sorry to leave the cold seas of the Southern Ocean behind. Two weeks later the ship anchored at Melbourne, and George Campbell described their arrival after a long sojourn at sea with his characteristic succinctness and wit: “There was joy among us on arriving at Melbourne. Of gales, snow, icebergs and discomfort generally, we had had enough, and the memory of a dinner I ate at the club the first evening, followed by the opera, yet lingers in my memory as one of the pleasantest experiences of a poorly paid and laborious career!” Still, the experiences in the Southern Ocean had not all been negative. Aside from the science accomplished, most on board relished the personal satisfaction of having seen things that few others had. Campbell went on to say that the voyage was worth the discomfort, for few people then living had ever had the pleasure of enjoying such spectacular iceberg scenery.

Challenger would spend most of the next two years in the Pacific. Her remit was to explore the deep ocean; Wyville Thomson later explained that he “rather discouraged” too much effort by the naturalists on land, especially if it took away from work at sea. But particularly for Henry Moseley, islands were like magnets. In the Pacific, Challenger would visit many islands that, while perhaps not as remote as some of those she had explored in the Atlantic and Southern Oceans, were much more exotic. They had an additional attraction: native people. Anthropologists—most of them European—had a fascination with people who were different from themselves, especially those they considered to be “primitive.” The scientists of the Challenger expedition shared that interest and that prejudice. Along with the fish, coral, insects, birds, rocks, and other natural specimens they collected, they brought back for further study tools, weapons, and decorative articles made by native people. They also collected skulls and partial skeletons of indigenous people from South Africa, South America, Australia, New Zealand, and various Pacific Islands; the human remains were later examined by anatomists, and their findings were written up in minute detail in the Challenger Report.

The context in which the Challenger scientists worked was vastly different from that of today, perhaps most strikingly in their interactions with indigenous people. The conventional wisdom at the time—at least among those in what we today refer to as “the West”—was that European civilization was superior to others, and probably always would be, a belief now referred to as cultural imperialism. Moseley’s treatment of native peoples, for example, was not much different from his approach to corals or penguins: the people, their customs, and their tools and weapons were objects of study, to be measured, described, and perhaps displayed in a museum. It is unsettling to come across frequent references to indigenous people as “savages” in his book about the expedition.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4782)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(4442)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(4293)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3937)

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid(3806)

Origin Story: A Big History of Everything by David Christian(3675)

COSMOS by Carl Sagan(3602)

How to Read Water: Clues and Patterns from Puddles to the Sea (Natural Navigation) by Tristan Gooley(3443)

Hedgerow by John Wright(3338)

How to Read Nature by Tristan Gooley(3313)

The Inner Life of Animals by Peter Wohlleben(3294)

How to Do Nothing by Jenny Odell(3285)

Project Animal Farm: An Accidental Journey into the Secret World of Farming and the Truth About Our Food by Sonia Faruqi(3206)

Origin Story by David Christian(3182)

Water by Ian Miller(3166)

A Forest Journey by John Perlin(3052)

The Plant Messiah by Carlos Magdalena(2911)

A Wilder Time by William E. Glassley(2845)

Forests: A Very Short Introduction by Jaboury Ghazoul(2822)